The Significance of Schooling and Cross-cultural Differences in Intelligence

As modern influences penetrate all remote corners of the world, the contemporary universal view is that if you introduce formal schooling to any group of rural people, they will learn to read and write. The knowledge and skills learnt through so many years of school will enable graduates to improve their personal lives, families, and contribute to nation building by working in the modern sector of the economy in manufacturing, agriculture, and other professions. In “The Significance of Schooling: Life‑Journeys in African Society”, Robert Serpell explores the impact of schooling on a rural community in Africa. The book explores some of the most troubling issues regarding the status of schooling in a typical rural African or other Third World countries. On the basis of data from the study, Serpell argues that it is erroneous to assume that all individuals who have, for example attended seven years of formal schooling any where in the world, acquire certain amounts of quantifiable knowledge and skills that will both predispose and prepare them to perform clearly predefined useful roles and achieve specified goals in the community. Because of reasons he explains in the book, the “Life‑Journeys” of individuals who attend formal school in rural Africa show remarkable differences in their life courses for many reasons. In many respects, what Serpell finds may have parallels to the impact of formal schooling on racial and ethnic minorities and non‑middle class communities in the American and other developed Western societies. The findings of the study are intriguing.

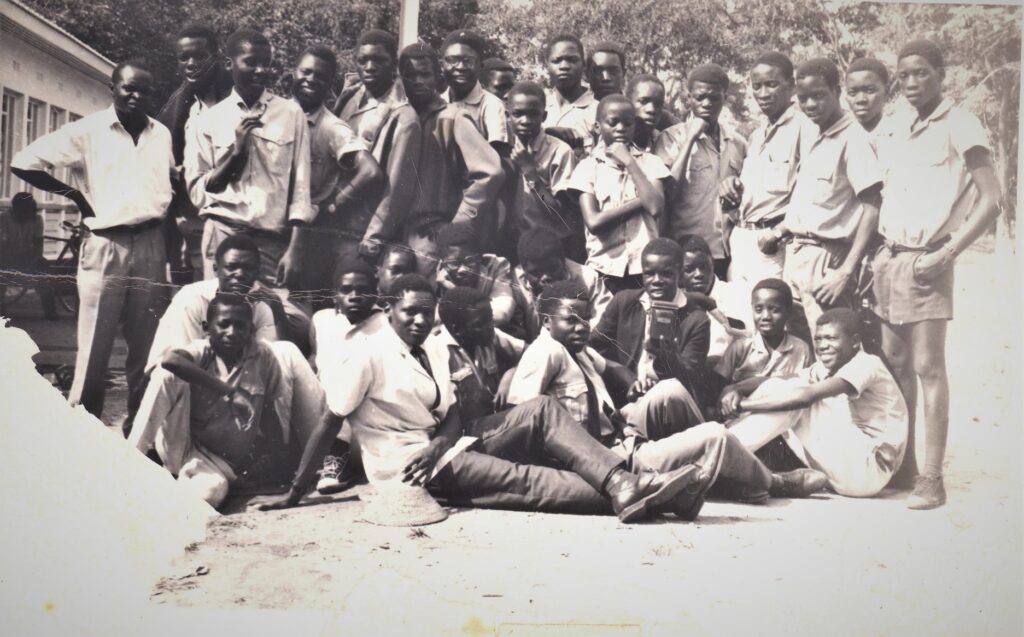

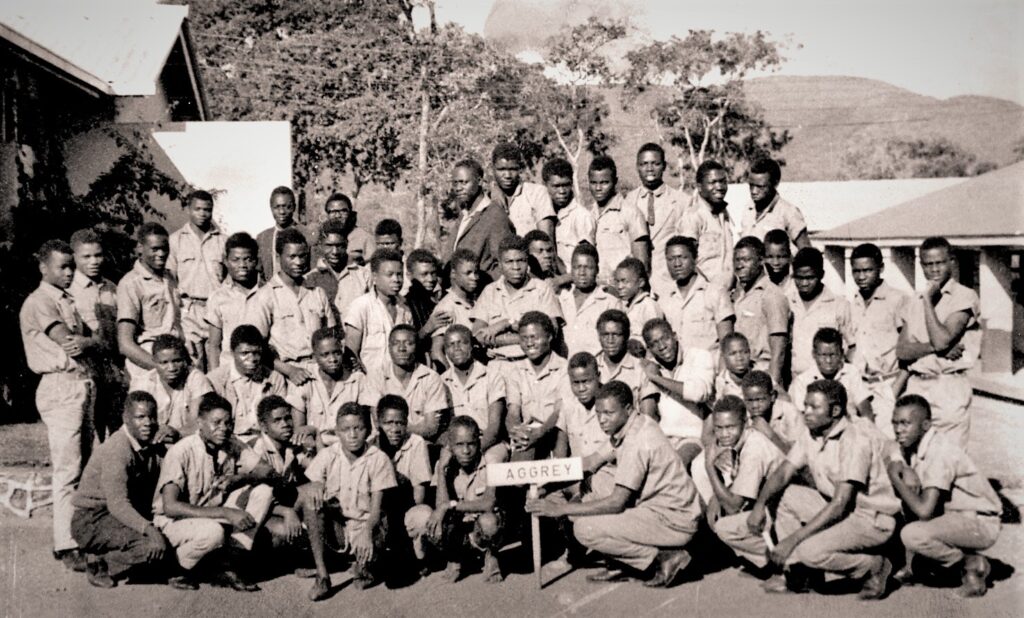

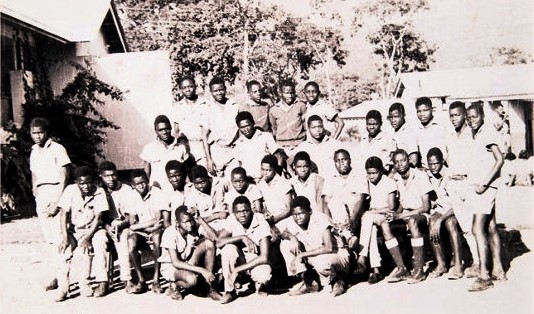

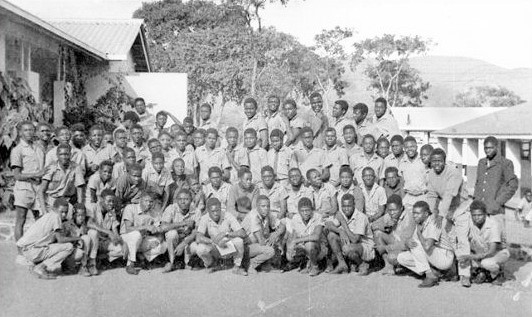

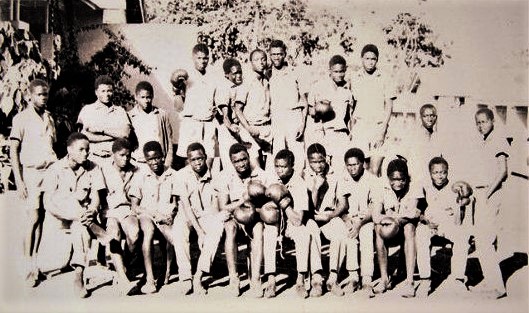

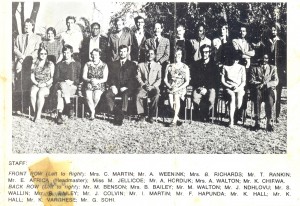

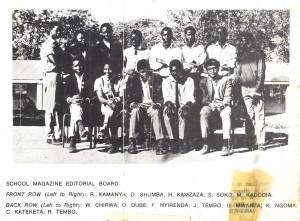

In “The Significance of Schooling”, Serpell presents findings from a longitudinal study he conducted at Kondwelani School among the Chewa people of Katete district in the Eastern Province of Zambia since 1973. The rich findings presented in the book are based on first, tracing the life experiences of a cohort of over twenty village boys and girls who attended Kondwelani School from their first grade in 1973 up to as far as they could go with formal education. Second, Serpell interviewed parents and surveyed teachers’ perspectives on the significance of schooling in the context of a rural environment.

The book has seven chapters which address such issues as “the multiple agenda of school in Zambia”, “Wanzelu ndani? A Chewa perspective on child development and intelligence”, “the formal education model of cognitive growth”, a description of the research cohorts’ “life‑journeys and the significance of schooling.”

Although it may seem common knowledge to scholars of cross‑cultural studies that people in various cultures of the world many define “intelligence” differently, this knowledge may not be fully appreciated by some scholars and policy makers outside the narrow confines of academia and the public in general. The publication of Murray and Herrnstein’s “The Bell Curve”* (1994) caused vituperative and searing controversy in the American society in 1994. In that study the findings that drew the most heated debate were that Asians had the highest levels of intelligence, Whites were second, and Blacks had the lowest Intelligence Quotients. Although Serpell’s study does not raise this issue directly, one is left to wonder how Murray and Herrnstein would react to these findings which strongly suggest the possible absurdity of their sweeping generalizations.

Among the many findings that are fascinating from Serpell’s longitudinal case study is that the Chewa people of Eastern Zambia define “Nzelu“, which is the closest linguistic equivalent of “intelligence”, very differently. However, he cautions the reader against treating the concept of “Nzelu” among the Chewa as being equivalent to “intelligence” in English. The latter in Western psychology seems to have an exclusively cognitive thrust. Among the Chewa people,

nzelu…appears to have three dimensions, corresponding roughly with the domains covered in English by ‘wisdom’, ‘cleverness’, and ‘responsibility’, or in French by ‘segesse’, ‘debrouillardise’, and ‘serviabilite’. Both literary and conversational usage draw on the contrast between the two dimensions ‑chenjela and ‑tumikila, and yet the full meaning of nzelu seems to embrace both of them. The central thrust of Chewa culture’s definition of nzelu is thus a conflation of cognitive alacrity with social responsibility.(p.32)

Another fascinating dimension of the study is that Serpell interviewed parents in the village and asked them to rank or evaluate the cohort of school children on the indigenous scale of nzelu or intelligence. The interesting findings were that the Chewa people rank their children. not according to the school abstract concept of intelligence which relies heavily and exclusively on cognitive manipulation of abstract symbols, but rather on such community criteria as whether the child can be sent by adult to carry out challenging tasks or chores, trustworthiness, attentiveness, and cooperativeness.

Serpell explores the significance of schooling in the lives of the research cohort in rural Zambia. He reports some important contradictions to the main stream expectations of the impact of schooling. For example, he finds that completing a certain number of years of schooling neither necessarily guarantees functional literacy nor appreciation and acceptance of the values that are engendered by school. Children’s success in school among the Chewa people has, what Serpell terms, “an extractive definition.” Attaining high levels of education, for example attaining twelfth grade to a college education, means that the individual has to leave the village and become alienated from her indigenous community and culture. The child who leaves often is seen as a loss to the family, the community, and the child is said to have become a “muzungu” or White man or European.

Serpell also finds that inspite the Zambian provision in the official national policy that both girls and boys will have equal access to formal education, social pressures and expectations are such that fewer girls from Kondwelani School research cohort went beyond a seventh grade education. Finally, Serpell finds that teachers and parents have a very rigid conception of what school is about; something formal with a rigid “staircase model” of progress, and its operation is beyond their control, influence and contribution. Determination of failure and success is narrowly done by performance on tests.

Serpell’s “The Significance of Schooling” in a rural community in Zambia case study raises some new interesting theoretical and pragmatic issues that are of great importance to all scholars particularly of cross‑cultural psychology and formal education in Africa and the Third World. On the theoretical level, the findings in this book do provide valuable ammunition to challenge and debunk the Western rather monolithic concept of “intelligence” which heavily and exclusively relies on formal school achievement, the manipulation of written abstract forms and often reified as a concrete entity that can be used to determine and predict the life‑journeys of all individuals. (Murray and Herrnstein, 1994) “The word ‘intelligence’, as the discussion of nzelu and other related terms in Chi‑Chewa …. should have made clear, does not stand for a thing: it is an abstract noun representing a quality of behavior: how people behave, not something they have. Once we stop thinking of intelligence as concrete entity, the absurdity of asking how much of it someone has got or how much of it was passed on to them by their parents becomes apparent.” (Serpell, 1993: p. 263)

On a pragmatic level, Serpell raises the question of how should, the rather limited formal educational skills that rural children acquire, be used to improve their lives in the village once they leave school? At the moment, the study suggests that school has a mixed bag of outcomes and draws a repertoire of reactions ranging from ambivalence about its relevance to the lives of the village community and the drawing of complete separate dichotomy between school and the culture of the village life. Besides a few positive outcomes, school seems to be a largely alienating experience in the sense that it does not teach students skills that may more directly and positively impact their lives. Learning is done in English which is a foreign high status language none of the children speak at home.

Toward the end of the study, Serpell did something unique and unusual. He tried to get teachers, village parents, local agricultural extension, and health officials to hold a public discussion to exchange views about some of the findings from the study. All participants in the public forum were either had a subdued reaction or simply played their expected parochial roles. However, community participatory drama and popular theater performed under a village tree generated incredible enthusiasm from villagers, teachers, and other community leaders of the church, political party and those who were employed in government‑related institutions. The animated discussions were about the crucial issues that were portrayed in the play but had also been exposed in the study.

As the reader might be aware, the book is rich with research knowledge that breaks new ground. I recommend the book for cross‑cultural studies, African studies, educational psychology and rural development in the Third World, and all scholars who are interested in the impact of main stream formal schooling on minority or underclass communities.

*********REVIEWED BOOK: Robert Serpell, The Significance of Schooling: Life‑Journeys in an African Society, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993, pp. 345, Hardcover 59.95 US dollars

*Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray, The Bell Curve:Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life, New York: The Free Press, 1994.

Stephen Fraser, (ed)., The Bell Curve Wars: Race, Intelligence, and the Future of America, New York: Basic Books, 1995.